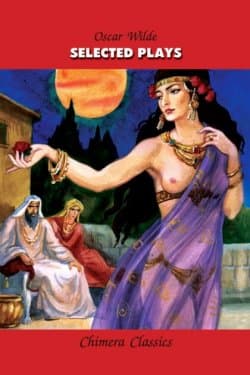

Selected Plays / Избранные пьесы - Оскар Уайльд (2003)

-

Год:2003

-

Название:Selected Plays / Избранные пьесы

-

Автор:

-

Жанр:

-

Серия:

-

Оригинал:Английский

-

Язык:Английский

-

Издательство:Антология

-

Страниц:19

-

ISBN:5-94962-036-4

-

Рейтинг:

-

Ваша оценка:

Selected Plays / Избранные пьесы - Оскар Уайльд читать онлайн бесплатно полную версию книги

LADY BRACKNELL. It is very strange. This Mr. Bunbury seems to suffer from curiously bad health.

ALGERNON. Yes; poor Bunbury is a dreadful invalid.

LADY BRACKNELL. Well, I must say, Algernon, that I think it is high time that Mr. Bunbury made up his mind whether he was going to live or to die. This shilly-shallying with the question is absurd. Nor do I in any way approve of the modern sympathy with invalids. I consider it morbid. Illness of any kind is hardly a thing to be encouraged in others. Health is the primary duty of life. I am always telling that to your poor uncle, but he never seems to take much notice… as far as any improvement in his ailments goes. I should be much obliged if you would ask Mr. Bunbury, from me, to be kind enough not to have a relapse on Saturday, for I rely on you to arrange my music for me. It is my last reception, and one wants something that will encourage conversation, particularly at the end of the season when everyone has practically said whatever they had to say, which, in most cases, was probably not much.

ALGERNON. I’ll speak to Bunbury, Aunt Augusta, if he is still conscious, and I think I can promise you he’ll be all right by Saturday. Of course the music is a great difficulty. You see, if one plays good music, people don’t listen, and if one plays bad music people don’t talk. But I’ll ran over the programme I’ve drawn out, if you will kindly come into the next room for a moment.

LADY BRACKNELL. Thank you, Algernon. It is very thoughtful of you. (Rising, and following ALGERNON.) I’m sure the programme will be delightful, after a few expurgations. French songs I cannot possibly allow. People always seem to think that they are improper, and either look shocked, which is vulgar, or laugh, which is worse. But German sounds a thoroughly respectable language, and indeed, I believe is so. Gwendolen, you will accompany me.

GWENDOLEN. Certainly, mamma.

(LADY BRACKNELL and ALGERNON go into the music-room, GWENDOLEN remains behind.)

JACK. Charming day it has been, Miss Fairfax.

GWENDOLEN. Pray don’t talk to me about the weather, Mr. Worthing. Whenever people talk to me about the weather, I always feel quite certain that they mean something else. And that makes me so nervous.

JACK. I do mean something else.

GWENDOLEN. I thought so. In fact, I am never wrong.

JACK. And I would like to be allowed to take advantage of Lady Bracknell’s temporary absence…

GWENDOLEN. I would certainly advise you to do so. Mamma has a way of coming back suddenly into a room that I have often had to speak to her about.

JACK. (Nervously.) Miss Fairfax, ever since I met you I have admired you more than any girl… I have ever met since… I met you.

GWENDOLEN. Yes, I am quite well aware of the fact. And I often wish that in public, at any rate, you had been more demonstrative. For me you have always had an irresistible fascination. Even before I met you I was far from indifferent to you. (JACK looks at her in amazement.) We live, as I hope you know, Mr Worthing, in an age of ideals. The fact is constantly mentioned in the more expensive monthly magazines, and has reached the provincial pulpits, I am told; and my ideal has always been to love someone of the name of Ernest. There is something in that name that inspires absolute confidence. The moment Algernon first mentioned to me that he had a friend called Ernest, I knew I was destined to love you.

JACK. You really love me, Gwendolen?

GWENDOLEN. Passionately!

JACK. Darling! You don’t know how happy you’ve made me.

GWENDOLEN. My own Ernest!

JACK. But you don’t really mean to say that you couldn’t love me if my name wasn’t Ernest?

GWENDOLEN. But your name is Ernest.

JACK. Yes, I know it is. But supposing it was something else? Do you mean to say you couldn’t love me then?

Диагноз смерти (сборник)

Диагноз смерти (сборник)  Маленькое отклонение

Маленькое отклонение  Пьесы (сборник)

Пьесы (сборник)  Трактаты

Трактаты  Коварная Саломея

Коварная Саломея ![Днем и ночью хорошая погода [сборник]](/uploads/posts/2019-08/thumbs/1565909303_dnem-i-nochju-horoshaja-pogoda-sbornik.jpg) Днем и ночью хорошая погода [сборник]

Днем и ночью хорошая погода [сборник]  Наследник

Наследник  Пир теней

Пир теней  Князь во все времена

Князь во все времена  Когда порвется нить

Когда порвется нить